Revisiting "Holy Grail" Bugs in Emulation

Debugging is not an easy task, and Holy Grail bugs are an exceptionally difficult class of bugs to squash. Discovering the root issue, figuring out the error in logic leading to the issue, and finally stamping out the issue without introducing new issues can be a long and arduous process. Sometimes one part can be easier than others, and sometimes every step is difficult. But common to all bugs is the required time, dedication, and ingenuity required.

It has been been a few months writing my first two articles on Holy Grail bugs, and it would seem that the articles piqued interest in these bugs, possibly bringing renewed dedication and new insights and ingenuity into the process. As such, some of the biggest, toughest bugs across multiple systems have now been solved, once and for all.

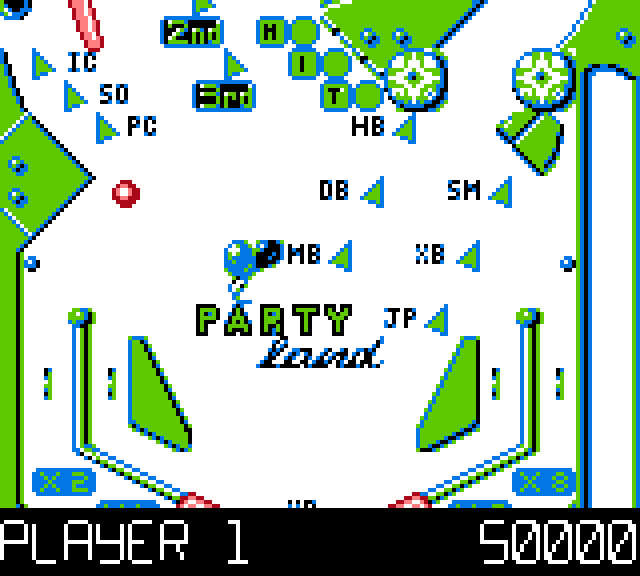

The Phantom of Pinball Fantasies ⬨

I had previously written about a bugbear for Game Boy emulation, Pinball Fantasies. With its complicated sequence of tightly timed IRQs almost always working, but one single misfire being enough to take down the entire game, it seemed like this bug might never be squashed.

After helping author the Pinball Fantasies section in the previous article, I noticed that Lior became very focused on solving the issue once and for all. A few months later, sure enough, he did solve the issue. Not only did it require accurate emulation of video timing and stat IRQ blocking, already two very difficult topics, the process brought to light the fact that Game Boy interrupt timing is far more complex than previously believed.

Gekkio released information and a test case demonstrating some very peculiar behavior involving how interrupts are processed: the cycle in which an interrupt is triggered is not the same cycle in which the type of interrupt triggered is observed. There is a one cycle window in which you can confuse the Game Boy’s interrupt system by changing interrupt parameters.

Interrupt processing on the Game Boy has three important pieces. The EI and DI instructions enable and disable interrupts globally, adjusting what is known as the IME register; the specific interrupt types that are enabled, known as the IE register; and the list of currently asserted interrupts, known as the IF register. The hypothetical flow for interrupt processing is fairly simple:

- Check if

IMEis on—that is, if interrupts are enabled globally. if not, continue normally. - Check if any bits set in

IFandIEoverlap by doing a bitwiseAND, and iff so an interrupt is triggered. - The least significant bit set of

IF AND IEinforms which interrupt is triggered. - Jump to the appropriate interrupt vector in memory for that interrupt type.

The big revelation here was that steps 2 and 3 do not occur at the same time. If you can manage to assert IF AND IE in one cycle and change one of the values before the interrupt vector jump occurs, strange things happen:

- If the least significant bit of

IF AND IEchanges during dispatch the jump is to the interrupt vector specified after the change. - Or, if

IF AND IEis zero during dispatch the CPU jumps to the reset vector at 0 instead of an interrupt vector.

This is a hyper-specific edge case that, much like other hyper-specific edge cases, seems to affect only one or two games. In this case, those games are Pinball Fantasies and Pinball Deluxe, which both use the same engine code.

Further, if this behavior is incorrectly emulated by assuming that asserting and then de-asserting the interrupt during the same instruction starts dispatch many games start to crash, such as Pokémon Pinball. Interrupt dispatch should only occur if the IRQ is asserted at the end of an instruction, and this edge case only occurs if the assertion changes mid-dispatch.

Lior also discovered that interrupt timing can appear to be delayed by a cycle while halted, but it depends on both the specific model of Game Boy and specific interrupt raised.

While it may sound strange for an interrupt to be delayed by one cycle, the exact reason for such a thing happening is fairly simple. The SM83 processor used in the Game Boy has two different types of timings: M-cycles, which are the instruction-level clock and occur at quarter of the master clock frequency, and T-states, which occur every master clock cycle and are sometimes referred to as sub-cycles due to the fact that they make up the separate steps taken by instructions. While an M-cycle can be thought of as the CPU performing one complete task, e.g. adding two numbers, T-states are even lower level. For addition, it may look something like this:

- Load value in register

Binto the arithmetic logic unit. - Load value in register

Cinto the ALU. - Perform the addition using the ALU.

- Store the result of the addition into register

A.

This is only an example however; it’s significantly less clear on the Game Boy how T-states lay out individual instructions and seems to be more relevant to how memory operations are performed than ALU operations.

So clearly if an interrupt is triggered it has to happen on one of these four T-states, right? All a delayed interrupt would mean is that the T-state on which an interrupt request is processed is before the cycle in which that IRQ is asserted. Take this example of T-state timing:

IF: 00,IE: 01, No IRQ assertedIF: 00,IE: 01, No IRQ assertedIF: 01,IE: 01, IRQ assertedIF: 01,IE: 01, IRQ asserted

If the IRQ check happens on T-state 3 or 4 then the IRQ occurs before the next instruction is processed. However, if the IRQ check happens on T-state 1 or 2 then the IRQ would appear to be delayed one cycle despite being asserted during the “previous” instruction. Indeed, different interrupt sources will assert on different T-state.

Due to the complexities involved in emulating T-states, plus the lack of requirement of emulating T-states at all for 99% of games, many emulators do not emulate at a T-state level, making this type of accuracy difficult to attain without “tricks” or hacks of some sort. But again, it seemed to be needed for Pinball Fantasies.

With most of that information now verified, Pinball Fantasies now runs in SameBoy. The same cannot be said of mGBA however, due to the current mess of the video timing implementation. Hopefully soon it will work in mGBA too, but for now it’s still beyond all but one accurate emulator.

The Great GBA DMA Disaster ⬨

Although I did not write a section on it in the previous articles on Holy Grail bugs, there was one bug that perplexed me for two years. Namely, there are a handful of games that use DMA from invalid memory (usually from the address 0) to clear regions of memory. VBA implements this pretty simply: if you’re doing a DMA from 0, then write 0 to the destination. This seemed sort of sensible, until I noticed that I could not get this same behavior to reproduce on actual hardware, no matter the configuration I used. The behavior was always different.

Let’s take a step back for a bit so we can truly understand how bizarre this bug is. Some of you reading this article probably don’t even know what a DMA is. It stands for direct memory access and refers to a piece of hardware that can perform memory transfers without using the main processor. The Game Boy Advance contains four different DMA channels, numbered 0 through 3. Each DMA channel can be programmed to do memory copies between addresses with various different start timings, such as immediately starting, or start on horizontal blanking. However, only one DMA can be transferring at a time, leaving the other suspended until it completes. Further, the main CPU is also paused while this happens.

The main uses for DMA on the GBA are a small list: transferring large chunks of data from the cartridge into main memory, doing EEPROM read/writes, copying video parameters every scanline (this is for example one way to create the faux-3D “mode 7” effects), or buffering audio. Different DMA channels have special purposes or restrictions, too, such as only DMAs 1 and 2 can be used for audio buffering, and DMA 0 cannot access the cartridge bus at all. DMA channel 3 is mostly used for general purpose “immediate” transfers, channels 1 and 2 for the two different audio channels, and channel 0 gets very little use.

All of the DMA channels can access RAM, but beyond that things vary. Documentation available online says that only DMA channel 3 can access the ROM, and none of the DMA channels can access the BIOS region of memory. But no documents refer to what happens if you try to do this. As previously mentioned, VBA writes 0 to the DMA’s destination, but what happens on hardware is not only nearly-completely detached from this implementation but is also far, far more complicated. In fact, when I first started trying to reproduce this bug on hardware, I never got zeroes filling the destination memory.

The first thing I observed was that trying to write an invalid source address to the DMA configuration register resulted in the DMA not actually updating the source address. After doing a DMA copy from a valid region later DMAs from an invalid region appeared to do another DMA from the old source. This seemed like a perfectly reasonable explanation at first: the reconfiguration just fails so it uses the old configuration. Yet this didn’t explain why several games expected zeroes to be written to the destination.

I sat on this bug for a while because I knew I needed to write hardware tests to figure out what was actually going on, but oddly enough those tests just seemed to prove that what I was doing was almost right. Never did I get out zeroes; I always got memory from the previous DMA’s source in the destination. Although these tests did prove fruitful for other reasons, as they showed a few shortcomings in documentation online, no matter how many tests I wrote or DMA configurations I directly took from which that did this, the result never was zeroes.

But then I noticed something that could only be explained in a very specific way. Namely, when doing a 32-bit transfer it would write out the same 16-bit value mirrored. But that specific value did not appear anywhere in the source. The 16-bit value appeared as part of a larger chunk of memory, but I was doing a 32-bit transfer. It was then that I realized that what’s going on isn’t that the source address isn’t being updated, it’s that the source data is being cached. The last value that the previous DMA copied was written out repeatedly. And due to the nature of the other tests I’d written this was never actually demonstrated.

It had seemed like the pieces were starting to fall into place…but I still wasn’t getting zeroes. And the games definitely expected zeroes from these configuration. Even looking at the previous transfers, they didn’t end with zeroes. There were still major pieces missing.

Then it clicked. Only one DMA can be running at a time. The cached value from the previous transfer is shared among all DMA channels. The DMA channels aren’t completely independent, so when one DMA finishes a transfer its last value is left in the cache, so if another DMA cannot access its source address…it uses the other DMA’s last value! I quickly tried implementing this and what I discovered was that suddenly every single one of the bugs relating to invalid DMA source addresses was fixed, all at once.

The awful, nasty truth is just that the DMA transfer register is shared between all four DMA channels. Since the audio DMAs were generally copying silence when this zero-writing occurs the cached value in the DMA buffer can be abused to write as many zeroes as desired wherever into memory.

Meanwhile, VBA just writes zeroes because that’s what the games use this edge case for. But now I know why.

The Improbable But Correct Lady Sia Bugfix ⬨

In the first Holy Grail bugs article I said the Lady Sia bug would haunt me to my grave, but I’m still alive and this bug isn’t. And despite my dramatic take on the magnitude of this bug the solution ended up being quite mundane. Slightly strange, but still mundane: my “best guess” in the previous article was that enabling a background layer was just latched for three scanlines, but it seemed like a particularly strange thing to take that long. Almost everything either take effect the next scanline or the next frame. Three scanlines was an obvious outlier so it sounded immediately wrong.

But when talking about this bug with another emulator developer, they dug up posts on the GBAdev forums about “garbage” for a few scanlines when meddling with background layers being enabled. So maybe it wasn’t outlandish after all. Well, I finally got around to writing a hardware test to see what the exact behavior of enabling a background layer mid-frame would be and…yep, it takes three scanlines. Sometimes fixes to high profile bugs end up being entirely anticlimactic, and indeed that was the case here.

Turns out fixing this bug also fixed another long-standing bug. Go figure.

A Slew of Corrections on the Nintendo DS ⬨

Before going much further I should write up some corrections to the previous article. I mentioned quite a number of DS games and included some recent developments in terms of bugfixes. However, I wrote that section of the previous article over a month prior to releasing the article and the landscape had shifted in the meantime. For example, the Tongari Boushi loading bug had been fixed in DeSmuME in addition to melonDS before I released the article, but around the same time as when I was writing it.

Further, I was using the most recent release of DeSmuME to research some of the existing bugs, but that release is apparently quite out of date so things had improved even on some of those bugs too.

There was also some confusion about which of the Pokémon Black/White bugs were anti-piracy measures versus just regular old emulation bugs, so I’d like to set straight what I believe to be the case:

- Booting at all requires partial emulation of the modified cartridge SPI bus. This is not an anti-piracy technique, most likely; it’s just making sure that saving and loading will work. There are codes floating around that will bypass this screen but as a result saving/loading are completely broken.

- Requiring the IR sensor to reply when getting EXP does sound like an anti-piracy technique to me, especially since I’m not aware of there being any IR functionality involved with single player battles.

- The game crashing if cartridge timing is wrong is also likely not anti-piracy and just a basic gameplay/level streaming technique that will break if the cartridge doesn’t have the same timing characteristics as the hardware it was written for. This sort of thing is actually quite common on consoles where you can get texture pops or missing assets if your disk drive starts aging, and this is likely just another manifestation of the same principle.

The Dénouement, or Something Like One ⬨

While us emulator developers keep chugging on bugs, the landscape keeps changing. Emulators for newer consoles are shaping up more and more each day, and seemingly impossible bugs get squashed more and more. Lior has recently been making great strides with Game Boy emulation in SameBoy, implementing previously unknown behaviors in the APU and PPU, and compatibility in newer generation emulators like RPCS3 has been improving by leaps and bounds.

Though it’s nearly impossibly difficult to emulate a console perfectly, at least without a hardware clone, we get closer and closer each day.

Postscript: A Several Month Late Explanation ⬨

Some of you out there may have also noticed that there hasn’t been a Patreon article since July, or that the Patreon was suspended at the last minute one month, or that mGBA progress has slowed down significantly.

I have had significantly less time recently to work on my hobby projects since I started a new job in August. While I do not intend to drop mGBA nor stop writing articles I am severely limited in how much I can do. As a result:

- The monthly article series is over. I’ll still write articles occasionally but I just don’t have the time to do them anymore with any regularity.

- My DS emulator, medusa, is suspended until further notice. I’d like to revisit it at some point, but until then there are several new DS emulators to look forward to in the meantime.

- Major mGBA releases are going to be very slow for the foreseeable future. Sorry, I just can’t fit working on large features into my schedule anymore so things are taking a lot longer than I expected. Though I intend to release mGBA 0.6.2 shortly that may be the last release for a while.

Work on mGBA will continue at a slowed pace and I do intend to get to several major new features, including netplay and a debug UI, sooner rather than later. However, “sooner” now means “Q2 2018 is optimistic”.